Response to Public Criticism

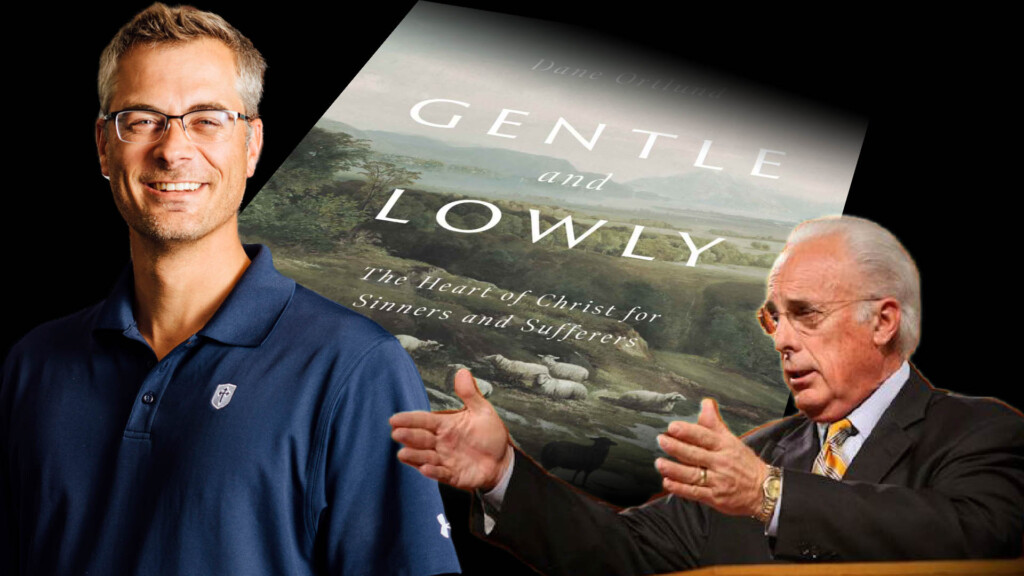

As much as Gentle and Lowly has been a gift of Gospel-centered discipleship and devotional reorientation in the chaotic, polarized church in the West, some within Reformed camps have criticized the book. To appreciate this book fully and critically, I would like to address some of those critiques here. I find that addressing counter arguments can be helpful to strengthen one’s position. I have found Gentle and Lowly to be profoundly fruitful and glorifying to God in my life. I seek to interact with some of the opposing critiques to further point out the strength of the book and the reasons Christians should not hesitate to read it.

The main critiques are generated by John MacArthur and his media company Grace To You. I have read through the Grace to You article several times. While the article, at times, states “despite the deficiencies and dangers we have highlighted, Gentle and Lowly does have some perceptive observations and profitable words of encouragement.” However they ultimately compel readers to avoid the book, stating its more bad than good and that its view of Christ is “imbalanced” and “dangerous.” Grace to You goes on to say that all of “Evangelicalism has lost all appetite for a full-orbed, biblical view of God. For at least one hundred years, compromising evangelicals have been attacking classic theism, while simultaneously trying to weaponize the terminology of charity, meekness, and humility in order to intimidate into silence any fellow evangelicals who speak out with clarity and passion about the dangers of Pharisees and wolves.”1

Others suggest that Ortlund’s book lies about God and that “To put one or two of His perfections up against the rest is to flatter the readers with the very real danger of lulling many of them into a false security that will remove the fear of God before their eyes and put them to sleep until they die, only to awake to His justice, judgment, and eternal wrath.”2

While I understand some of the theological nuances and questions that should be discussed and considered, I don’t find the critiques against the book to be substantial, intellectually helpful, or furthering the mission of the book – to share the powerful love of God in the Gospel in a way that captivates and transforms lives in the Kingdom of God.

A few things to note.

This book is not dangerous. Reading it will not lead to one abandoning the faith or losing their salvation. It will not cause them to wildly misread the Bible or embrace unhealthy theological positions. It has its own interpretational stances just as any other book does, but these are not of major, orthodox concerns for Christians seeking to embrace the Gospel more and more in their lives.

two kinds of theological studies

Biblical Theology, first and foremost, follows the message of Scripture. It is concerned with studying the Text in the original language, studying the genre, phrases, author, and audience, understanding the surrounding historical context, and recognizing the ultimate Story of the Bible.

Systematic theology participates in many of these things too, yet is is more concerned with synthesis: it works towards logical organization of truth, modern relevance and application, and highlights the details and dialogue between various texts. In other words, Biblical theology is primarily concerned with what the Biblical author meant and what the inspired Text means while systematic theology predominately focuses on constructing an infrastructure of truth from the various texts of the Bible

Don’t get me wrong, systematic theology is important and good. As one pastor writes on TGC:

“Biblical theology without systematic theology misses much of the propositional truth each text reveals. In my observation, too often the emphatic “storyline” approach fails to produce a more comprehensive understanding of the written Word. Biblical theology gives us the breadth of redemptive history while systematic theology gives us the depth. Biblical theology focuses on the progressively revealed storyline of God’s Word. Systematic theology gathers the texts and truths that accompany—and are tucked into—that storyline so we can gain more complete and nuanced insight into God’s mind.”

Shorey later concludes: “Without systematic theology we cannot peer deeply into these issues. Instead, our lack of comprehensive awareness of Scripture will truncate our understanding and render our conclusions superficial at best.”3

These two disciplines are interconnected, yet also distinct. Systematic Theology seeks to correlate the messages and principles of Scripture in a way that makes the most comprehensive sense. To do this, systematic theology often has to answer questions the Bible does not give explicit answers to, synthesize and harmonize differing ideas, and give explanation to things that are not fully certain. Meanwhile Biblical theology is more focused on the message of the Bible itself-that is, the intended meaning of the writer, the way the audience would have read the text, and the inspired authorship of the Spirit.

In an interview, Vern Polytrhess points out that these two disciplines are perhaps more connected than some people think. He states:

“Different people have had different conceptions of both biblical theology and systematic theology, so it is wise to ask what people mean in both areas, as well as to look at the relation between the two areas.

I would myself describe systematic theology as study of the Bible’s teaching in which we try to synthesize and then summarize what the Bible as a whole teaches about all kinds of topics—God, man, Christ, sin, salvation, and so on.

In some contexts the expression “biblical theology” simply means theology built on the Bible; that is, it is systematic theology done in the right way. But there is also another possible meaning. Biblical theology, as described by Geerhardus Vos, studies the Bible with a focus on its history, the history of revelation and of redemption. Whereas systematic theology is topically organized, biblical theology is historically organized. It looks at the progress of God’s work and his revelation through time. In addition, biblical theology more broadly conceived can study the themes that are distinctive to a particular book of the Bible, or to books written by a single human author (for example, Paul’s letters). At their best, biblical theology and systematic theology interact and help to deepen one another.”4

The controversy over Dane Ortlund’s book is far more troublesome and problematic for Reformed systematic theology than anything else. Dane Ortlund raises some good discussion questions and reflections on theological concepts in a few areas, but this does not disqualify him or his book. Gentle and Lowly is more concerned with the Biblical Theological message on the heart of God than it is with the Reformed systematics that find tension and issue with certain passages he beautifully exposits.”

As one theologian suggests, Biblical theology centers on seeking the message of the author to the audience and the Text, while systematic theology seeks to build and construct an infrastructure of beliefs and corresponding rationale.

Reflecting on Geroge Buchanen’s autobiography and his own experience, Streett writes: “Using metaphorical language, Buchanan likened his fellow faculty members to “collie dogs” who spent their time keeping the sheep within the fold and rounding them up whenever they strayed. Their main job was to protect the theological borders of their institutional pasture. By comparison, Buchanan identified himself as a “hound dog” who followed the scent of biblical truth wherever its trail might lead.”

Within his role as a Biblical theologian, Streett explains:

“As a biblical theologian, I am trained to study each book of the Bible on its own—to examine it in its unique literary, historical, and social contexts. Bible scholars do not try to harmonize the Gospels, for example, because we know that each book is unique. Their authors wrote at different times to different audiences located in different parts of the empire, lived under different leaders, and experienced different levels of persecution. The authors wrote for distinct reasons and had distinct goals in mind, selecting only the stories about Jesus and his teachings that were helpful and pertinent to their respective audiences.”5

He goes on: “That is not to say traditional understandings of certain doctrines should be set aside on a whim. But neither should we hesitate, based on solid research, to seek further light on any given subject. After all, it was the re-examining of Scripture—in comparison with established Catholic creeds—that ultimately led to the Protestant Reformation and its widespread distribution of the Bible to the common believer.

Some systematic theologians focus on church councils and the historical development of creeds, many of which were formulated in response to specific heresies (such as Docetism and adoptionism) and have been upheld and defended for centuries. And while biblical scholars can repeat and affirm the Nicene and Apostles’ Creeds without reservation—standing in unity with the church universal—our task is different from systematic theologians.

The main question we are concerned with is, What did the text mean to the original audience? We focus on the first-century text and seek to acquire more historical and cultural insights. Otherwise, the entire field of biblical studies would remain static, and no fresh readings or analyses would emerge. In other words, our primary job as biblical scholars is to interpret the text rightly; and we are often happy to leave the doctrinal implications in the hands of systematic theologians.

That said, even the best hound dogs can occasionally find themselves barking up a wrong tree. But we must not allow that possibility to hinder us from our overall task. So, I urge my fellow hound dogs to keep their noses to the ground and follow the trail of biblical truth. Amazing and exciting discoveries—leading to a better understanding of Scripture—are just beyond the horizon.”6

danger, heresy, and the orthodox essentials

My point in spending so long discussing BT vs. ST is to point out that critics of Gentle and Lowly have not brought their issues forward with nuance. Instead of pointing out how their systematic theological stances are challenged by Ortlund’s positions within a Biblical theological study, some instead dogmatically assert his book opposes their views (views that they wholeheartedly assert are THE true and only way to read the Bible and view theology). Therefore, because of this, his book is out of bounds of any reader who REALLY cares about the Gospel and Bible. The problem with this is two-fold. First, it is troublesome that there is no room for charitable discussion or disagreement under a broader unity from some Christian denominations and groups. If one’s stance towards every other theologian and differing academic interpretation of Scripture is to say: “to be a Christian you have to have MY interpretation of the Bible ” there is a problem. They have perhaps conflated the inspiration and inerrancy of the Bible with their own fallible interpretation of the Text.7 Furthermore, while discussion over the points of disagreements below is important, a dogma that calls anyone and everyone with a different view a false teacher, heretic, or dangerously wrong because they disagree with your interpretation is foolish and counterproductive to the Kingdom of God. To expand orthodoxy (conversely to expand attacking claims of heresy against everyone who disagrees with ones expanded orthodoxy) is similarly problematic as those who diminishes the tenants of orthodoxy of the church to almost nothing.

Historical theologian Michael J. Svigel identifies this problem within the modern church. He reflects: ““In another vein, some evangelicals associate the term “orthodox” with their own doctrinal systems. That is, they believe the detailed beliefs of their particular church or denomination alone represent orthodoxy. This is especially true of complex theological systems expressed in doctrinal statements, confessions, catechisms, or consistent patterns of interpretation. Too often evangelicals believe that their seemingly airtight systems perfectly express both the big picture and the details of the Bible, rendering their system alone as pure theology. This means, of course, that everything else is heresy—or at least polluted doctrine. The result of this kind of narrow orthodoxy is often a graceless dogmatism leading to mean-spirited debates over every minor point of disagreement.”

Svigel goes on to define orthodoxy as the following: “I wish it were as easy as holding up the Bible, pointing, and saying, “That’s it. That’s orthodoxy. Doubt it at your peril.” That would be a misunderstanding of the term “orthodoxy.” The word means “ correct opinion,” and relates specifically to the tried and true interpretations of the Bible’s major theme, its overarching story, and its foundational truths. These are the fundamental beliefs of the Christian faith that never change—and never should. They correspond to that cluster of teachings Vincent of Lérins had in mind when he wrote in AD 434, “We hold that faith which has been believed everywhere, always, by all.” These core truths of Christianity, which have endured throughout history, constitute the essence of orthodoxy. Practically, orthodoxy becomes the framework within which we faithfully read the Bible as Christians.”8

Svigel lists seven core tenants of orthodoxy that have been held to in all places by all major parts of the church throughout history: “These seven areas of doctrinal continuity demonstrate that the basic contours of orthodoxy can be discerned throughout the history of the church. The Triune God as Creator and Redeemer. God is a trinity—one divine essence in three persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. All things have been created and will be redeemed from the Father, through the Son, and by the Spirit. The Fall and Resulting Depravity. Due to the disobedience of the first man and woman, all humanity and creation fell into a state of depravity, unable to save themselves. The Person and Work of Christ. The eternal Son of God became incarnate through the Virgin Mary and was born Jesus Christ, fully God and fully human, two distinct natures in one unique person. He died as a holy substitute for sinners, rose victoriously from the dead, ascended into heaven, and will come again as Judge. Salvation by Grace through Faith. Because of humanity’s depravity, people are unable to save themselves. Therefore, grace is absolutely essential to salvation, resulting in faith in God and eternal life. Inspiration and Authority of Scripture. The Holy Spirit moved the prophets and apostles to compose the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments, the inspired, authoritative norm for the Christian faith. Redeemed Humanity Incorporated into Christ. The church is Christ’s body of elect, redeemed, baptized saints who by faith partake of the life and communion with God through Jesus Christ in the new community of the Spirit. The Restoration of Humanity and Creation. One day yet future, Jesus Christ will physically return to earth as Judge and King. All humanity will be resurrected bodily—those saved by Christ unto everlasting blessing, the wicked unto everlasting condemnation. The physical creation itself will also be renewed, and sin, death, and evil will be eternally vanquished. Together, these seven essential truths tell a compelling story of creation, fall, revelation, redemption, and ultimate consummation from the Father, through the Son, and by the Holy Spirit. This narrative focuses on the immovable center of Jesus Christ, whose incarnation, death, and resurrection destroyed death and brought the hope of salvation. Finally, along the way the church has re-emphasized the markers of orthodoxy—councils and creeds that defended the Christian concepts of the Trinity, Christ’s person and work, sin and grace, and the basic content of Christian orthodoxy.”9

This long tangent on orthodoxy is all to point out that Ortlund’s book does not take us out of bounds from our historical, Christian faith. Not by a long shot. Ortlund offers a different interpretation (one that suggests that maybe the Biblical authors and their words are not merely reduced to complete anthropomorphic language). This should initiate discussion, not cries of heresy and shouts of danger from other theologians.

One pastor reflects on Grace To You’s Review by saying the following: “I would have loved to see this review as a caution. I would have loved to see this review raising questions. I would have loved to see this review suggest that, if a reader is not careful, he or she could draw theologically incorrect conclusions. After all, any book that focuses us on a single aspect of the heart or character of God could lead a reader to believe that the attributes of God are parts, thus denying divine simplicity, the oneness of God. All that God is, God is. There is not part of God that is love and part of God that is wrath. God is God, fully, all the way through. And God does not change so that emotions are stirred in him the way that ours stir in us.

“I would have loved to see this review remind believers not to allow an emphasis on the love and mercy of Christ to confuse one regarding Christ’s attitude toward sin. God hates sin. We should too. And we do not want to allow our embracing of the depth of Christ’s grace to allow us to think that Christ has ever loved sin. This caution could have been raised without mocking or out-of-context quotation.”

“I love GTY and the ministry of John MacArthur. I believe that the church would be far better were we to learn far more from him. And I will certainly not let this review prevent me from continuing to learn from and grow from that ministry at GTY. But I’m disappointed. I’m disappointed because the review is just not even-handed, not gracious, not honest in its depiction of G&L. I found G&L, a book I was given at the Shepherds’ Conference in 2020, a lovely read, something I intend to read again, because it helped me to love the mercy of Christ. I’ll certainly reread G&L with the cautions in mind. But I know already that my first reading of G&L did not even begin to make me think false things about the Lord or his nature.”10

Another pastor and theologian from TGC Africa states: But I believe there’s another reason behind some of the more antagonistic reactions to Gentle and Lowly. It’s what Timothy Keller calls the spirit of the elder brother, in his Prodigal God. Contrast with the younger brother, who doubts that the father can forgive him, the older brother resents the unconditional love that his father extends to his sibling. Keller puts it perfectly when he says that the older brother loses out on the father’s love because of his own obedience and fidelity. He writes: “It is not his sins that create the barrier between him and his father, it’s the pride he has in his moral record; it’s not his wrongdoing but his righteousness that is keeping him from sharing in the feast of the father.”

In closing, I’m not saying that the more zealous critics of Gentle and Lowly are lost in their own confusion and rejection of God’s spectacular love. But I am suggesting that their disapproval of Ortlund’s book might not in its essence be a theological one. Haven’t all of us said or thought, with the older brother: “Look, these many years I have served you, and I never disobeyed your command…But when this son of yours came, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, you killed the fattened calf for him?” (Luke 15:29-30) I wonder if this isn’t the feeling that partly lies behind some Christians’ disapproval of Ortlund’s book. That God’s overwhelming love means he meets us with open arms, regardless of who we are or what we’ve done.”11

Perhaps, the rigid theological boundaries of some groups prevent them from being willing to enjoy the profundity of the love of God presented by Ortlund (ultimately attested in the Scriptures themselves!) Perhaps, the protection of a house and foundation of systematic theological dogma is more important than the Gospel message to a Western people who have significantly missed the beauty of the Gospel. I have not found Grace To You’s critique to be academically useful as a seminary student who enjoys deep theological dialogue and exegesis. I have not found it fruitful or edifying as an apprentice of Jesus who yearns to embody more and more of the character of the Triune God in all of his life. But let’s review the concerns.

the three main critiques

There are three main concerns with Ortlund’s book presented by GTY and others.

- Ortlund cherry picked the Puritans.

- Ortlund describes God’s character and emotions being in conflict with each other; this challenges the divine nature of God

- Ortlund rejects or contradicts divine impassibility.

To the first concern, I would suggest that a book focused on one aspect of God’s character (one that Biblical theology and Ortlund’s exposition would suggest is central to His being) MUST be selective in pulling quotes. There are publisher standards and boundaries to follow in writing. Gentle and Lowly could have been a 1000 page book, covering the Puritan’s entire thought process and theological ideas on God and His character. But that is not the point of the book. I’m sure Ortlund would be the first to encourage anyone to read the Puritans for themselves. But his book is a focused reflection on the Biblical message of God’s heart with select commentary from the Puritans who soaked in that same message of God’s love.

The next two concerns are more complicated. As stated above, these are not issues of orthodoxy/heresy and so Gentle and Lowly is not “dangerous” and a “significant departure from classical theism” of an orthodox, Christian view. The second concern is that Ortlund challenges the doctrine of divine impassibility. This is the belief that God is unchanging and -by extension – untouched or unmoved by humanity.

What is important to affirm about divine impassibility is that God experiences emotions in a divine, dispositional manner, not a human one. As one pastor argues: “Immutability and Impassibility are key, historic attributes the church has confessed, attributes that distinguish the infinite and eternal Creator from the finite and temporal creature. Immutability means God does not change in any way; he is unchanging and for that reason perfect in every way. Impassibility, a corollary to immutability, means God does not experience emotional change in any way, nor does God suffer. To clarify, God does not merely choose to be impassible; he is impassible by nature. Impassibility is intrinsic to his very being. Impassibility does not mean God is apathetic, nor does it undermine divine love. God is maximally alive; he is his attributes in infinite measure. Therefore, impassibility guarantees that God’s love could not be more infinite in its loveliness. Finally, impassibility provides great hope, for only a God who is not vulnerable to suffering in his divinity is capable of rescuing a world drowning in suffering.”12

What must be distinguished is that “God is impassible but not unemotional.” One TGC theologian writes:“If it is true that human beings can have a relationship with God which is both just and caring, then God must be capable of entering into our pain. In order words, it is all about compassion and “empathy.” However, it is not merely the understanding of pain per se, but the overcoming of it is what all sufferers really want. The analogy of a doctor and a patient capture this well. We indeed do not want a doctor who is only capable of sleeping in the bed next to his patients, and then mourns and groans with them. Rather, we need a doctor who understands our pain and then is able to take action in curing it. The incarnation and the resurrection of Christ reveal God’s compassion and solution for human sufferings and pains…the doctrine is not a barrier to understanding God’s compassion, but is in fact the assertion that his compassion is always fully available and functioning. Impassibility may not be something that we need to think about very often (when things are going well, we usually take them for granted), but it is vitally important. As Christians we need to appreciate where divine impassibility fits into the overall picture of God’s saving work.”13

Thus, perhaps, Ortlund should be challenged to consider if conflicting emotions is a necessarily human and sinful experience or if there is some way that God’s emotions can clash. Another consideration is whether or not God in His perfection, power, and knowledge, self-limits in any capacity. Some would suggest His love leads God, who exists outside of time, to step into time, space, and emotion to be in covenantal relationship with us. However, at this point, the discussion has moved towards systematic/philosophical theology, and has long left the message of the Gospel behind for abstract doctrinal debate. Yes, the character of God is important and must be discussed. But the God who identifies Himself as love (1 John 4:7) out of all the other attributes…surely He wants to us to understand the depths of His loving character.

It is not as if Ortlund is not aware of this difficult theological concept. In one of the footnotes, he address this topic:

“The name theologians give to the way the Bible speaks of God’s emotional life is anthropopathism. This is parallel to anthropomorphism, in which the Bible uses human terms to speak of God in ways that cannot be taken literally, such as speaking of God’s “hand.” Anthropopathism is a little trickier. By it we mean to protect the fact that God is not like us in our emotional fickleness; rather, he is completely perfect and transcendent and not affectable by circumstance in the way we finite humans are. He is “impassible.” At the same time, we should not so write off the way the Bible speaks of God’s inner life (with terms such as anthropopathism) that we make God a basically platonic power divorced from the welfare of his people. The key here is to understand that while nothing catches God off guard, and nothing can affect God from outside of God in a way that threatens his perfection and simplicity, he freely engages his people through a covenant relationship and he is genuinely engaged with them for their welfare. If you find the notion of divine “emotion” unhelpful, think instead (as the Puritans put it) of divine “affections”—God’s heart-disposition to embrace his sinning and suffering people. To further explore the way God is both impassible and yet capable of emotion, see Rob Lister, God Is Impassible and Impassioned: Toward a Theology of Divine Emotion (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2012).”14

Ortlund is not opposed to healthy and extensive systematic theology, but it is not his predominant focus within his book. But even he points out that we should take a moment to consider these concepts and study them further. It’s interesting that Ortlund warns against a rationalist, platonic view of God that removes from Him all the emotion which He Himself ascribes to Himself within the Bible. Again, I suggest Ortlund is following the testimony of the Text and being critiqued by systematic theology critics -of a certain kind – without a lot of unifying charity or nuance.

Finally, the third concern is a good set of questions to discuss that are an extension of the second issue. Are the emotions of God at conflict with each other? Or in other words, is it a solely human and sinful experience to have mixed emotions that clash with each other? How do emotions operate within the divine nature of God? This is a classic systematic theology question. We can compile Biblical input and then synthesize them towards an answer. Yet, in my opinion, we are beginning to reach the edge of human comprehension. What is clear is that God has emotions. Again, these are dispositional, not based on need but out of His care and love for people. The transcendent God of the universe, existing outside of time and self-sufficient (an eternal God who doesn’t inherently NEED us) enters into time and space to create, to redeem, to save, and to love humanity and the world. What is clear is that He chooses to actively pursue and bring us into relationship with Him. In this sense, perhaps, He chooses to be touched by us, moved by us, to feel emotions concerning our situation. Or perhaps He experiences and has emotions in a way we can never understand – in a way beyond time and space. But, whether God’s nature is inherently emotional or something He chooses out of love, the Bible is not clear on. This is a reflection into the divine nature that is somewhat mysterious and beyond us.

As one theologian rightly notes: “This is also the reason why we must understand that the biblical accommodations or anthropopathisms are based on analogy. Analogy means similarity, but not equivalence; otherwise it is not an analogy but a definition. God’s repentance is not an emotion of his Being but a change of treatment towards mankind from a human point of view. Thus, as to God’s love and all other emotions—jealously, hate, etc., we then must say that they are an analogy of our emotion. Something about men is analogous to something in God because we are his image-bearers. God indeed has emotion, but his emotion is far beyond and even not the same as our emotion. Divine impassibility presents, first of all, the transcendence of God’s emotion, or, borrowing Paul Hem’s term, themotion: “A themotion X is as close as possible to the corresponding human emotion X except that it cannot be an affect.”15

concluding thoughts

God’s transcendence is an important topic to consider and discuss within the context of His heart and the Gospel. While Grace To You is right to bring up this consideration, their claim that Ortlund goes too far in his ideas and claims is really more of a statement that he is going outside Reformed Systematic Theology boundaries. And as stated before, orthodoxy is far broader than Reformed Theology.

Furthermore, does Ortlund really “lean heavily on some of the empty, therapeutic jargon that dominates postmodern evangelical culture”? Depends on who you ask. Many praise Ortlund’s book for addressing a society that seeks the powerful love of the Gospel message while rejecting the church and Christian faith who know and share that love. And whether you like it or not, we are all in the postmodern world. Some react within the postmodern world with streaks of fundamentalism and a stubborn clinging to modernism. Others shift with the changing tides. But both groups are people of postmodernity. Who is to say what is the perfect balance of cultural engagement? This is no simple task for the church at hand. Who’s to say whose words are “empty”? I have often found that the loudest, most dogmatic, black-and-white critics of postmodern engagement are also the ones who don’t realize they too are apart of the postmodern world in one way or another; they are also the ones who are the least nuanced and equipped to engage with various cultures and people groups within the post-modern landscape.

Overall, the book is worth reading. And one can do so without diving into the depths of ST research on divine impassibility, the transcendence of God’s divine emotion, and anthropomorphism. These are important topics within theological dialogue and conversation, but they are not the point of Gentle and Lowly. Unfortunately, large swaths of Christians in the American West know with their heart and being so little of the powerful, radical, transformative love of God. They have cognitively been educated about it and parroted doctrinal positions on it. But how many daily encounters anew the mightily- affectionate love of God that the New Testament writers extol again and again, pray for churches to experience and comprehend again and again, emphasized in book after book of the Bible? Ortlund seeks to give fresh perspective to a modern landscape too cognitively-familiar with the love of God while overall their affections, functional dispositions, and lives go unchanged, unmoved, and untouched by the Gospel. My hope is that everyone will read Gentle and Lowly with fresh eyes and humble hearts, willing to let Ortlund challenge their perspective and deepen their appreciation for the heart of the Triune God.

- https://www.gty.org/library/blog/B210315 ↩︎

- https://warhornmedia.com/2022/01/26/the-false-teaching-of-crossways-gentle-and-lowly/ ↩︎

- https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/systematic-theology ↩︎

- https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/justin-taylor/the-relationship-between-systematic-theology-and-biblical-theology ↩︎

- https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2024/february-web-only/biblical-theology-evangelical-seminary-institutions-scholar.html ↩︎

- https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2024/february-web-only/biblical-theology-evangelical-seminary-institutions-scholar.html ↩︎

- A helpful discussion on American Christianity and the doctrine of Inerrancy for those who are wanting to learn more. https://www.holypost.com/post/episode-491-american-democracy-american-inerrancy-with-michael-f-bird ↩︎

- Svigel, Michael J. RetroChristianity: Reclaiming the Forgotten Faith, ch. 4, Apple Books. ↩︎

- Svigel, Michael J. RetroChristianity: Reclaiming the Forgotten Faith, ch. 4, Apple Books. ↩︎

- https://pastortravislv.com/2021/03/16/my-sadness-over-the-grace-to-you-review-of-gentle-and-lowly ↩︎

- https://africa.thegospelcoalition.org/article/whats-wrong-with-gentle-and-lowly ↩︎

- https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/essay/immutability-impassibility-god ↩︎

- https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/themelios/article/the-impassible-god-who-cried/ ↩︎

- Gentle and Lowly, 72. ↩︎

- https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/themelios/article/the-impassible-god-who-cried ↩︎

Leave a comment